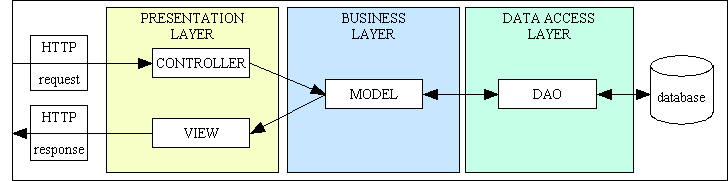

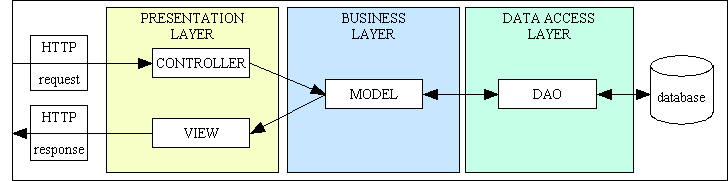

Figure 1 - MVC plus 3 Tier Architecture

Since a major motivation for object-oriented programming is software reuse (refer to Designing Reusable Classes for details), classes should be developed so that they will be reusable. This is because the more code you can reuse for common tasks then the less code you have to write, and the less code you have to write to get things done then the quicker you can get things done. How do you recognise code which can be converted from duplicated to reusable? You look for repeating patterns in either structure or behaviour, where there are similarities mixed with differences, and you try to put the similarities into reusable modules and separate out the differences. An experienced programmer will tell you that the differences in an application are often isolated to the business rules for each entity, while the similarities, which can repeat over and over again and which act as wrappers for the business rules, are often referred to as boilerplate code. A well-written OO application should therefore reduce the amount of this boilerplate code which has to be written so that the developer can spend more time on the business rules which are important to the business.

The amount of reusability you have in your code can be measured by the code you don't have to write, or don't have to write more than once. It is also better to have complete modules at your disposal rather than a collection of snippets which you have to assemble like a jigsaw. The first step is to create a library of reusable code which you can either call from within your application code or can inherit. The next step, which can only be achieved by a really skilled programmer, is to create a framework (such as RADICORE) which calls the code which you write, thus implementing The Hollywood Principle - "Don't call us, we'll call you." The best pattern for this principle is the Template Method Pattern which uses boilerplate code defined in an abstract class. It also contains calls to empty "hook" methods which can be customised in individual concrete subclasses.

A novice programmer is prone to writing code which is full of mistakes or inefficiencies for one simple reason - they don't know any better. This is where the more experienced programmers, who have made mistakes and found ways to avoid them, step in and provide guidance so that novices can learn from their experiences and thus avoid wasting time on the same mistakes. This "advice", the practices of experienced programmers, is often labelled as best practices, but this can be misleading. These practices are not subject to peer review, so anybody is free to publish their own personal versions, with different programmers able to produce conflicting advice. It is also worth mentioning that common practices followed by a bunch of poorly trained Cargo Cult programmers do not have the same value as those followed by really experienced programmers who know how to think for themselves instead of letting somebody else do their thinking for them. I have been told by my critics on many occasions that if only I followed their advice that I would be standing on the shoulders of giants, but as their advice is full of flaws I would regard it as paddling in the poo of pygmies

.

While some people regard these "best practices" as rules which every programmer should follow without question in a dogmatic fashion, there are certain practices which apply to only a subset of the available programming languages, so rules for compiled and statically typed languages may be totally irrelevant for interpreted and dynamically typed languages. Other rules may be limited to a particular type of application and may be inapplicable to other types. For example, I only ever design and develop database applications which interact with users via electronic forms, and for the last 20 years I have concentrated on internet applications which use HTML at the front end and SQL at the back end, and my language of choice has been PHP. When I started I had no knowledge of a set of universal best practices which I was supposed to follow, so by using trial and error I created my own set which produced the least amount of errors and the most amount of reusable code. In 2003 I began to publish some of my own experiences, and shortly after I began to be criticised by other developers for not following "best practices", or rather their version of best practices. I regarded their criticisms as advice not rules, so I ignored anything which, in my opinion, would pollute my existing code base or reduce the amount of reusable code which I had at my disposal. In this article I will identify some the "best practices" which I deliberately ignore and explain why I have chosen to do so.

So exactly how much of the boilerplate code in an application can be made reusable? 5 percent? 10 percent? 50 percent? If you look at the diagram in Figure 1 you will see that the RADICORE framework uses four types of component that appear in the most common architecture for database applications - the Model, View, Controller and DAO (Data Access Object). Which practices a developer follows, and how each of those practices is implemented will have a direct bearing on how much code within those components will be reusable.

The conformist way is to follow what the "experts" teach you without question as they have - in theory - done all the necessary thinking for you. This usually results in software with the following characteristics:

You should be able to see that each of the four components requires a lot of hand-crafting, so there is little opportunity for reusable code. I see the biggest problem as the failure to recognise patterns followed by the propensity for writing code which is tightly coupled and has low cohesion. In the above scenario, for example, Each Controller is tightly coupled to a particular Model, and each Controller can handle several transactions for that Model where some of those transactions are repeated for other Models.

Another thing you should notice is the number of times an object has multiple responsibilities:

To my untrained eye the words responsible for more than one

sounds suspiciously like a violation of the Single Responsibility Principle (SRP).

Note that the fact that a DAO can handle any number of tables does not violate SRP as it does not have code which mentions any specific table. The table's name is provided as an input argument, and the same code can work with any table regardless of its name or structure.

My approach to writing code was totally different. I did not follow the examples given by other programmers as I could see considerable room for improvement. Instead of Controllers which handled multiple transactions with multiple Views for a single Model I created Controllers which handled only a single transaction with a single View for a single Model. I am still following the MVC design pattern, but with an implementation which is totally different from anyone else's. The decisions I made to get to this implementation were based on the following observations:

I judge my implementation, which is based on my personal interpretation of good programming principles, to be better than the best which is produced by others simply because of the higher volume of boilerplate code that I wrote just once yet can share over and over again. All the reusable code which is supplied in my framework is as follows:

The above list identifies all the reusable components which are supplied by the framework and which cover 100 percent of the boilerplate code. The only code which has to be included by the developer are the business rules which can be inserted into any of the "hook" methods which have been defined in the abstract class with empty implementations but which can be overridden with custom implementations in any concrete subclass.

So what effect does all this reusability have on a developer's productivity? The RADICORE framework was designed to speed up the development of web-based database applications, so once you have created a table in your database how much effort does it take to build a family of transactions to view and maintain the contents of that table? Answer: this job can be completed in just 5 minutes without having to write a single line of code - no PHP, no HTML and no SQL. If you don't believe me, or think that your framework can equal or better that, then I suggest you take this challenge.

I first entered the world of Information Technology (IT), or Data Processing (DP) as it was known then, in the 1970s simply by passing an aptitude test that showed I had a logical mind. As a junior programmer I followed the instructions I was given, but as my knowledge increased I began to see holes in those instructions where the logic was weak. There was no such thing as a universal set of programming standards or best practices that everyone was taught and was expected to follow, as every team had their own set of standards, either at the whim of the current project/team leader, or, even worse, handed down by ex-programmers-now-management whose ideas were out of date. As I moved from one team to another it was commonplace for the standards to be completely different and sometimes contradictory. It came to a point on one project when I could not complete the program I was working on to my satisfaction while following the standards to the letter, so I ignored them and did what I thought to be the most pragmatic and practical. A short while later a senior consultant from another team carried out an audit on the project which involved seeing how various programs were written, and his opinion of my program was quite telling:

In an audit against the project programming standards this program is not very good however, in the auditors opinion, this is one of the best written and documented programs of all those examined.

This raised an important question in my mind - If I could ignore a set of "best practices" and still produce software that was recognised as being "better than everyone else's", then how could those practices deserve the title "best"?

As I worked on more and more programs I began to notice repeating patterns, blocks of code which were either identical or very similar, but none of the teams maintained a central library of reusable code, so all I could do was keep a private copy of several programs as exemplars of those patterns so that I could use them as the starting point for new programs. In this way I could reuse the same basic structure but only have to amend the data names. It wasn't until I became a senior programmer at a software house which specialised in COBOL on the HP3000 that I began to create a central library of reusable subroutines that could be called instead of copied. I also began to document my personal coding standards. When I became team leader I began to teach my team members how to use my subroutine library, and this immediately removed the source of some common programming errors and increased their productivity. My bosses took note of this and adopted my personal coding standards as the company standards. As time went on I added more and more functions to my library which I eventually turned into a framework after being asked to design and build a Role Based Access Control (RBAC) system for a major client in central London. All the documentation for this can be found on my COBOL page.

Writing computer software is like writing a book - it is a work of authorship which requires a creative mind. Computer programs work on structure and logic, so it requires people who can determine the structure and logic of a problem and convey that in the instructions which they present to the computer. Programming is an art, not a science, and as such you cannot be successful at it unless you have talent. Unfortunately a large number of people who call themselves programmers do not have the basic talent, so they attempt to disguise this fact by following the rules set by others in the hope that by doing so they will replicate their levels of workmanship. The truth is the exact opposite. By following these rules blindly and without question, by not understanding why each rule exists and what problems it was meant to solve they end up by being nothing more than Cargo Cult Programmers. These people cannot replicate the success of others, instead all they can do do is produce broken facsimiles. I do not follow this trend. Instead of following the rules set by others in a dogmatic fashion and hoping that the results will be acceptable I prefer a more pragmatic approach in which I find a solution which produces the best results and modify my rules accordingly. To me the best results can be measured by the quantity of reusable software which I can produce. In this paper I identify the various practices which I employ in my framework and compare them with those which have been approved by the paradigm police in order to show why my results, which produce a higher volume of reusable software, can be regarded as being superior.

While building my RADICORE framework I began to publish articles on my personal web site to document what I had achieved, but very quickly I was accused of the heinous crime of not following best practices

. I asked where these practices were documented only to be told that there was no single definitive source as various "experts" had posted their own contributions in random places on the internet or even in a variety of books. In a lot of cases there was no access to the original source of a particular practice, just to somebody's second-hand interpretation of what that practice meant to them. A lot of practices had been reduced to simple buzzwords, such as favour composition over inheritance

, which did not properly identify the problem they were supposed to solve nor prove that the solution was actually effective. The absence of a proper problem description and proof that the solution given was actually the best available did not convince me that the barage of "advice" had any merit, so I ignored it.

I decided to ignore certain practices when I deemed them to be irrelevant for reasons such as:

I also chose to ignore certain practices which were expressed in a single sentence without any explanation. When I am told you must follow so-and-so rule

I always ask Why? Where is this rule documented? What good thing happens if I do follow this rule? What bad thing happens if I don't?

For example, I ignore the practice program to the interface, not the implementation

as it makes no sense to me. I cannot simply call a method without identifying the object that implements that method. I could never find any sample code which proved that this idea had any merit, so I did not know how to implement it.

Another example is favour composition over inheritance

which is useless without a description of precisely why inheritance is bad. It took me a long time to find an answer - you may inherit from a class that contains an implementation which you do not want. The solution is obvious to me - if something is bad then don't do it, don't inherit from a class which contains an implementation that you do not want. One way to achieve this is to only ever inherit from an abstract class, but apparently not many programmers are good at creating such abstractions. This is what Ralph E. Johnson and Brian Foote wrote in Designing Reusable Classes:

Useful abstractions are usually created by programmers with an obsession for simplicity, who are willing to rewrite code several times to produce easy-to-understand and easy-to-specialize classes.

Decomposing problems and procedures is recognized as a difficult problem, and elaborate methodologies have been developed to help programmers in this process. Programmers who can go a step further and make their procedural solutions to a particular problem into a generic library are rare and valuable.

Does this mean that my skills are "rare and valuable"?

With my very first attempt at inheritance I created an abstract superclass which I could share with every concrete subclass, and this turned out to be the correct thing to do. I was not taught how to do it, I just did it as it seemed the most sensible thing to do. Not only has this abstract class NOT caused any problems in the past 20 years, it has become the backbone of my framework as it provides a huge amount of boilerplate code which can be shared by hundreds of table classes; it provides huge amounts of polymorphism which I can utilise with my own version of dependency injection; and it allows me to implement the Template Method Pattern on every call from a Controller to a Model which in turn allows me to override "hook" methods in any concrete subclass to provide custom processing.. This is something that I could not achieve with object composition.

There is a limited set of principles which I regard as being relevant to any programming paradigm which are not tied to a particular language or type of application. These are as follows:

The principle of High Cohesion where Cohesion refers to the degree to which the elements inside a module belong together. All my early programs were monolithic in that all the code for the user interface, business rules and database access was mixed up in a single unit. When I switched to UNIFACE I was exposed to a multi-tier architecture, first 2-tier and then 3-tier with its separate Presentation, Business and Data Access layers which, coincidentally, is an exact match for the Single Responsibility Principle (SRP). I immediately saw the benefit of splitting up the code in this way, which is why I used it as the basis of my sample application while I was teaching myself PHP, which at the time was version 4. I later combined this with the Model-View-Controller design pattern when I split the code for dealing with the HTTP request from that which produced the response.

Note that using an OO language automatically produces a 2-tier architecture. After you have created a class with properties and methods which models an entity which will be of interest in your application you will need a second component which instantiates that class into an object so that it can then call methods on that object. As the Model will contain multiple methods this second component will control which methods are called and in what sequence, hence it is given the name of Controller.

Please also refer to What Coupling is NOT and The difference between Tight and Loose Coupling.

Note here that these are general principles which can be applied to any programming language. All the projects I had worked on in the 20 years prior to my switching to PHP had their own private set of development standards which were often completely different from those used by another project. When I eventually became project/team leader I produced my own development standards in which I only accepted those practices which, in my experience, produced the best results. I flatly refused to follow other people's ideas in a dogmatic fashion and instead adopted a more pragmatic approach where each practice had to prove itself before I would even consider it.

When I started teaching myself PHP I had to get to grips with its object oriented capabilities. I started with the following definition:

Object Oriented Programming (OOP) involves writing software which is oriented around objects, thus taking advantage of Encapsulation, Inheritance and Polymorphism to increase code reuse and decrease code maintenance.

I interpreted this statement as follows:

$this which gives it access to other properties and methods within the same object.More of my opinions can be found in What Encapsulation is NOT.

More of my opinions can be found in What Inheritance is NOT.

More of my opinions can be found in What Polymorphism is NOT.

The technique for identifying duplicated code which can be turned into reusable code is described in The meaning of "abstraction". This requires examining code looking for patterns so that you can separate the similar from the different, the abstract from the concrete. Only then can you consider placing the similar into reusable modules and the different into unique modules. Note that this process can only be performed on code that already exists - you cannot perform an abstraction out of thin air and then write the code that implements that abstraction. As Johnson and Foote wrote useful abstractions are usually designed from the bottom up, i.e. they are discovered, not invented

.

Within any program there are basically two categories of code - the unique business rules and the non-unique boilerplate code. This has also been referred to as glue code. This topic has also been addressed in Write Only Business Logic: Eliminate Boilerplate. It is this non-unique boilerplate code which should be considered as a prime candidate for being moved into reusable modules which can be called from many places instead of being duplicated in many places.

As I built the code for my sample application I tried different ways of achieving results and opted for the ones which produced the simplest and best results, and which maximised the amount of reusable code. When I was "advised" that I should be following other practices (which had been approved by the paradigm police) I quickly saw that either I did not have the problem for which they were the solution, or that I had already implemented a simpler and more effective alternative.

A reasonable person might consider that following these basic principles would be an easy thing to do, but they would be wrong. You would be amazed at how some people can take a statement and interpret it in so many different ways. Other people are incapable of developing good practices of their own, so they fall back to following practices which have been published by others. They fail to understand the problems which these principles or practices were designed to solve, and they do not understand when their usage is appropriate or inappropriate. By following rules invented by others without question in a dogmatic fashion they are in great danger of becoming nothing more than Cargo Cult Programmers. They are like swimmers in the sea next to a sewage outlet - they aren't actually swimming, they are just going through the motions.

Since a major motivation for object-oriented programming is software reuse (refer to Designing Reusable Classes for details) it is possible for the competence of an OO programmer to be measured by the quantity of reusable code which they can produce. As explained above in Reusability any code which is non-unique can be considered as a candidate for reuse. As I have already created a set of practices which has resulted in 100% of this non-unique boilerplate code being made available in reusable modules, I see no reason why I should switch to a different set of practices which have the effect of reducing those levels of reusability. I do not care about following practices which have been approved by the paradigm police, I only care about results. This means that in my world a practice can only be called "best" when it produces the best results, when it produces the maximum amount of reusability.

While developing my sample application I began publishing the results of my experiments on my personal web site only to be bombarded with accusations that I wasn't following "best practices", such as the following:

program to an interface, not an implementation, but as I don't use object interfaces I found it impossible to do so.

When I stated programming with PHP I knew nothing about the SOLID and GRASP principles, or Design Patterns, which is why I took no notice of them. Instead I relied on my own intuition and experience. My critics keep insisting on telling tell me that if only I followed their "advice" I would be standing on the shoulders of giants

, but the poor quality of their teachings leads me to believe that if I did I would in fact be paddling in the poo of pygmies

. I already had the ability to spot patterns in my code, and to then refactor those patterns into reusable software, so I am not willing to sacrifice what works for me on the say-so of a bunch of dogmatists and mis-guided know-it-all code monkeys.

Since a major motivation for object-oriented programming is software reuse, then this raises the following questions:

Here are my answers:

I shall first explain what I achieved before going into how I achieved it. Figure 1 below shows the basic structure of my framework and all the applications that run beneath it:

Figure 1 - MVC plus 3 Tier Architecture

As I said earlier I started with the 3-Tier Architecture, but a quickly spotted that the code for receiving the HTTP request was completely different and separate from that which returns the response, which is why I split the Presentation layer into two separate parts which then produced an implementation of the Model-View-Controller design pattern.

According to the Evans Classification the objects in the RADICORE framework fall into one of the following categories:

An Entity's job is mainly holding state and associated behavior. The state will be persisted in a database. Examples of Entities could be Account or User. In a database application each table is a separate entity in the database, with its own business rules, so its methods and properties should be encapsulated in its own class. That class will typically have several public methods which allow the state to be loaded, queried, updated and deleted.

Entities will exist as objects in the Business layer shown in Figure 1 above.

A Service performs an operation. It encapsulates an activity but has no encapsulated state (that is, it is stateless). It usually performs its operation on data obtained from an entity. Examples of Services could include a parser, an authenticator, a validator and a transformer. The class for a service will typically have a single public method so that it will produce a single output from a single input.

Services will exist as objects in the Presentation and Data Access layers shown in Figure 1 above, but there may also be some in the Business layer.

While Value Objects may exist in other languages they do not exist in PHP. Instead all variables/properties are held as primitive data types (aka scalars) or arrays.

The components in the RADICORE framework as shown in Figure 1 above can be classified as follows:

Using this small number of reusable components I have constructed an ERP package known as the GM-X Application Suite which is comprised of the following:

It should also be noted that:

The correct way to build application subsystems with RADICORE should be to follow these steps:

You should notice that the generated table class file initially contains nothing but a constructor which loads the contents of the table structure file into the common table properties in order to transform the abstract class into a concrete class. All the processing will be carried out by one of the common table methods which are defined in and inherited from the parent abstract class. These are the invariant methods which form part of the Template Method Pattern which may be interspersed with customisable "hook" methods into which the developer may add custom code. In this way the standard boilerplate code in the parent abstract class can be augmented with different custom code in each concrete subclass.

When the transaction generation procedure has been completed you will be able to find the newly-created task on either a MENU button or a NAVIGATION button and then run it. This is achieved simply by pressing buttons and without writing any code - no PHP, no HTML and no SQL. Only basic validation can be performed at this stage - any additional validation or business rules will need to be added manually by inserting the relevant code into one or more of the pre-defined "hook" methods.

If you not believe that working transactions can be created within 5 minutes without writing any code then I dare you to take this challenge.

There is an online Tutorial which will guide you through all the steps used to create the Sample Application.

I did not plan all these practices in advance, instead I followed a "suck it and see" approach. I practiced encapsulation with my first database table to produce an object in the business layer (which later became the Model) to handle all the business rules for that table, then wrote two scripts in the presentation layer, the first to receive the HTTP request and call the relevant methods on the Model, and the second to produce the response by running an XSL transformation. After copying these scripts to deal with a second table there was a lot of duplicated code, so I moved the code in the two Models into an abstract class which I could then share using inheritance. Because all communication from my Controllers to my Models was via methods which were defined in the abstract class this opened up the path to polymorphism which I took advantage of using my own version of dependency injection.

According to some OO aficionados, which includes Robert C. Martin (Uncle Bob) in his article NO DB, the "correct" way to build a database application in an OO language is to design and build the software first using the rules of Object-Oriented Analysis and Design (OOAD), then build the actual database last to fit in with the software. This requires the use of mock database objects during development, which then need to be replaced when the physical database is eventually built. In their minds the rules of OOAD are supreme and the database is just an implementation detail. What these people fail to realise is that databases need to be designed to take into account the rules of data normalisation which, as far as I am concerned, are far more logical and superior to those of OOAD. The two design methodologies are incompatible, which leads to a condition known as Object-Relational Impedance Mismatch which is often "cured" with that abomination known as an Object-Relational Mapper (ORM). By following the principle of Prevention is better than Cure I prefer to design my database first then build my software to match this design. In this way there is no mismatch and no need for an ORM. This matches what Eric S. Raymond wrote in his book The Cathedral and the Bazaar:

Smart data structures and dumb code works a lot better than the other way around.

The Logical Design phase of a project produces two outputs - a list of all the functions that the system must perform, plus the data structures that will be used to support those functions. This design exists on paper only, and must be discussed and agreed before the database is built and any code is written. In this way it is known what data the system will need to store and how it will be used. It is only then can you can start writing the code, which means that it is the software which is the implementation detail.

To build an application with the RADICORE framework you build the physical database first, then import its details into the Data Dictionary. From there you press buttons to create a separate class file for each database table. This produces two files - a table class file and a table structure file.

I keep each table class synchronised with its structure by means of a table structure file. If the structure of a table changes all I need do is rebuild this file.

For more details on this topic please refer to the following:

When I first read about the practice of using mock objects I thought it was a stupid idea, and I still do. When building a database application it was suggested that you build a mock object for each database table which you access during development, and only build the physical database and a "real" object once the code has been completed and tested. The idea behind this was that it was highly likely that the database structure would change during development due to the addition or deletion of either individual columns or entire tables, which would require the constant resynchronisation of the code which used that structure. I had a similar problem in COBOL many years ago, but I solved it when I realised that I could extract the table's structure from the database, write it to a text file, then add that file to a copy library which could be imported into a program whenever it was compiled. Instead of having to manually update a table's structure in my code all I had to do re-extract the data and recompile the program. In UNIFACE the procedure was slightly different as the table structures were maintained in a special database, which formed part of the IDE, known as the Application Model which was used as the input to all form components.

For my PHP framework I developed my own version of the Application Model which I called a Data Dictionary into which I could import the database structures from the database's INFORMATION SCHEMA, From there I can export the details into a table class file and a table structure file which will be used by the application. If the database structure changes all I have to do is rerun the import/export procedures and the two will be synchronised automatically. This makes the use of a mock object a complete waste of time.

In my humble opinion modelling the "real world" is only appropriate when you are writing software which actually interacts with objects in the real world. When you are writing a database application you are writing software which interacts with objects in a database, and those objects are called "tables" which hold nothing but data. You are not manipulating anything other than the data which is held on those objects. Each table has its own class which then becomes the Model in the Model-View-Controller design pattern. The contents of each table is viewed and maintained using any number of user transactions.

Each database and its associated set of transactions comprise a separate subsystem within RADICORE, each having its own subdirectory in the file system, below the root directory, to hold all its disk files. The framework itself is comprised of four core subsystems (Menu, Audit, Workflow and Data Dictionary). New application subsystems can be added at any time as extensions of the framework. The Data Dictionary subsystem is used to create new transactions, and the Menu subsystem is used to provide a login to the system, show the user which transactions they are allowed to access, list these transactions in menu pages, and then to run those transactions when they are selected.

While each subsystem has its own set of business rules which are unique, there is a lot of other code which is required to ensure that the right business rules are executed at the right time. Any of this similar non-unique code, known as boilerplate code, is potentially sharable, and it is these similarities which can be used used to identify areas of reusability, as described below:

If you ask the question What are the pillars of OOP? more often than not you will see four parts to the answer - abstraction, encapsulation, inheritance and polymorphism. In my humble opinion abstraction should be excluded from this list because of the following reasons:

While there are numerous different definitions for abstraction as far as I am concerned they are all useless as they do not get to the point. The only truly meaningful definition I have ever seen is the following:

Abstraction is about examining several objects looking for similarities and differences so that the similarities can be placed in a reusable module and all the differences placed in unique modules.

This topic is discussed further in the following:

I wasn't until several years after I had developed the third iteration my framework in PHP having produced separate versions in my two previous languages that I came across references to software design patterns. These were promoted as the best thing since sliced bread in the world of programming as they were reusable solutions to commonly occurring problems in software design, so I decided that they warranted some investigation on my part. I started by reading articles written by other programmers on how they had implemented certain patterns, and the first thing I noticed was that different programmers had produced totally different implementations of the same pattern. The second thing that I noticed was that I could not see how any of those implementations could be fitted into my framework, so I ignored them. I saw many references to the Gang of Four (GoF) book, so I decided to splash out and buy a copy so that I could get the facts directly from the horse's mouth instead of the second hand (mis)interpretations of a bunch of amateurs.

Up until that point the only pattern that I had encountered was the 3-Tier Architecture when it began to be supported in the UNIFACE language (as described in this article), so I was intrigued to see what other patterns existed. I was surprised to see that the 3-Tier Architecture was not listed, and as I read through the list of 23 design patterns I could not see anything that I could use in my code. This caused me to put the book on a shelf where it gathered dust for many years.

Later on I came across references to the Model-View-Controller (MVC) design pattern when other PHP programmers described their own implementations, but when I looked at their code it was so alien to me that I could not see any similar patterns in my code. This caused me to believe that MVC was not a pattern that I could use, so I forgot about it. It was not until some time later that a colleague wrote to me and explained that my code actually contained an implementation of the MVC pattern, and when he pointed me to a description of that pattern which simply identified the requirements of the three components without confusing the issue with any sample implementations I could see the wisdom of his words. I had originally build my framework around the 3-Tier Architecture with its Presentation, Business and Data Access layers, but as I had split my Presentation layer into two separate parts - one which received the request (the Controller) and passed it to the Model and another (the View) which extracted the data from the Model and displayed it to the user in the desired format - I had accidentally produced an entirely new implementation of the MVC pattern which combined the features of two different patterns.

My critics - of whom there are many - take great pleasure in pointing out my lack of ability when it comes to design patterns. They tell me that I am not using enough patterns, I am not using the right patterns, and that the patterns which I do actually use are not implemented correctly. I developed my code without any knowledge of patterns for the simple reason that my aim is to write code that works and to refactor it afterwards to minimise bugs and maximise reusability and maintainability. If patterns can be recognised in my code then that is by accident and not by design (pun intended). If my critics cannot see instances of their favourite patterns it is probably because either I could not find a use for those patterns or my implementation is so different from theirs that they didn't know what they were looking at. As far as I am concerned a pattern should not be used unless you actually have the problem for which that pattern was designed otherwise you are filling up your program with useless code. This mirrors the advice given by Erich Gamma, one of the authors of the GOF book, in the article How to Use Design Patterns in which he said:

What you should not do is have a class and just enumerate the 23 patterns. This approach just doesn't bring anything. You have to feel the pain of a design which has some problem. I guess you only appreciate a pattern once you have felt this design pain.

Do not start immediately throwing patterns into a design, but use them as you go and understand more of the problem. Because of this I really like to use patterns after the fact, refactoring to patterns.

Later on he gave some additional advice regarding the over use of patterns:

One comment I saw in a news group just after patterns started to become more popular was someone claiming that in a particular program they tried to use all 23 GoF patterns. They said they had failed, because they were only able to use 20. They hoped the client would call them again to come back again so maybe they could squeeze in the other 3.

Trying to use all the patterns is a bad thing, because you will end up with synthetic designs - speculative designs that have flexibility that no one needs. These days software is too complex. We can't afford to speculate what else it should do. We need to really focus on what it needs. That's why I like refactoring to patterns. People should learn that when they have a particular kind of problem or code smell, as people call it these days, they can go to their patterns toolbox to find a solution.

A major problem I have with design patterns is that they do not provide any reusable code, they are just vague descriptions for which the developer is expected to provide their own implementations. This means that the effectiveness of each implementation is down to the skill of the developer and not that of the pattern designer. I dived into the world of OOP with the intention of using my experience, expertise and intuition to provide as much reusable code as possible. I used my ability to spot repeating patterns in my code and used the technique of programming-by-difference, which I later found described in Designing Reusable Classes which was published in 1988 by Ralph E. Johnson and Brian Foote, to place the similar into reusable modules and the different into unique modules. This allowed me to create working implementations of several patterns, as shown in Figure 1, which enable developers who use my framework to reuse those implementations when constructing their own applications. All the boilerplate code is provided for them, so they only have to insert custom code into the relevant "hook" methods to deal with any non-standard business rules.

More information on this topic can be found in the following:

I had been using inheritance quite successfully in my framework for several years before I heard the mantra favour composition over inheritance which is also known as the Composite Reuse Principle (CRP) (which should be called CRAP in my opinion). All I read was that inheritance was bad and caused so many problems that should be avoided at all costs, and that object composition should be used instead. However, I could never find a description of these so-called problems, nor could I find any code samples which provided the proof that one method was better than the other, so I ignored this "advice" as I considered it to be not worth the toilet paper on which it was printed. It was several more years before I could find any more details on these alleged problems, and it turned out that there was never any problem with inheritance other than the majority of programmers were using it incorrectly. Inheritance only causes a problem if any of the following conditions are met:

The correct way to use inheritance, as described in Designing Reusable Classes, is to only ever inherit from an abstract class. This then enables the use of the Template Method Pattern which can provide all the necessary boilerplate code and allows custom code to be added into any concrete subclass using the "hook" methods which have been predefined in the abstract superclass. This level of functionality cannot be duplicated using object composition or object interfaces.

Please refer to the following for more information on this topic:

I taught myself how to program with PHP by reading the manual and by finding tutorials on the internet. I decided to repay the community by posting articles of my own regarding such topics as how to create XML files and how to perform XSL transformations, but when it came to describing my abstract table class a critic crawled out of the woodwork to tell me that "real OO programmers don't do it that way", but as he failed to identify what was wrong with my approach and what the "right" method looked like I dismissed his critique as the ravings of a lunatic. I had already used that code to build several table classes with great success, and I could not see how that code could be improved in any way.

Later on I was told that some real world entities have information which is split across several tables which are arranged in a hierarchy, and that all these tables should be handled in a single aggregate object where access to each table in the aggregation should go through the aggregate root. The result of this is a single class which handles several tables, such as in the following:

Databases do not have aggregate roots. You do not have to be in the table at the top of the hierarchy in order to access a member of that hierarchy, each table is an separate entity which can be accessed directly.

Please refer to the following for more information on this topic:

I created my first framework in COBOL in the 1980s. I first had to design a MENU database to hold all the information needed to implement a dynamic menu system and a Role Based Access Control (RBAC) system. This had a table called M-TRAN to hold the details for each user transaction within the application. When a user selected a transaction this executed the CALL instruction on the transaction's entry_point to activate the relevant subprogram. This required static code in the menu program to convert each selection into a subroutine call as it was not possible to construct and execute a dynamic CALL statement.

When I created the PHP version of this framework I used a similar database design in which I renamed this table to MNU_TASK. Instead of a column called entry_point it used script_id to identify a page controller in the file system. This is because PHP is not a compiled language which links all the subprograms into a single executable, it is an interpreted language where the individual transactions are independent and self-contained scripts which are activated by a URL which is submitted to the remote web server. Switching from one script to another is done by using the header('Location: <script_id>'); function which causes the web server to locate that script in the file system and then run it. Note that the 'Location: <script_id>' argument is a simple string which can be constructed dynamically instead of being hard-coded.

In my initial implementation I had a separate Controller script into which the name of the Model was hard coded, but later I found a way to take the name of the Model out of the Controller script and move it to a separate Component script. This meant that the Controller script could now be reused with any Model.

After completing my framework I was advised by some so-called OO "experts" that I should be using a front controller along with a router and a dispatcher to emulate how things were done in "proper" languages. When I looked at the code necessary to implement a front controller I could see straight away that it was more complicated that it need be, so I decided to ignore it. Why on earth should I write code to duplicate what is already being done by the web server? Rasmus Lerdorf, the founder of PHP, had this to say in The no-framework PHP MVC framework:

Just make sure you avoid the temptation of creating a single monolithic controller. A web application by its very nature is a series of small discrete requests. If you send all of your requests through a single controller on a single machine you have just defeated this very important architecture. Discreteness gives you scalability and modularity. You can break large problems up into a series of very small and modular solutions and you can deploy these across as many servers as you like.

When I later read the rules of Domain Driven Design and discovered that each use case (transaction) should have its own method I realised that by doing so I would remove huge volumes of reusable code from my framework which would defeat the purpose of using OOP in the first place. My framework contains vast amounts of polymorphism which allows me to call the same set of methods on many different objects using the mechanism known as dependency injection. My implementation was the result of the following logic:

The end result of this series of logical steps is that instead of having a separate custom-built Controller which is tightly coupled to a particular Model, and where each Model can only be accessed by a particular custom-built Controller, I have managed to produce a library of 45 reusable Controllers, one for each Transaction Pattern, which can be used with any table class. Each task (user transaction) in the application requires a particular Model to be linked with a particular Controller, and this linking is provided in a different component script in the file system. This is the file which is identified in the URL which is processed by the web server.

Any programmer worth his salt should be able to see that I have achieved this level of reusability by providing a standard set of method names within an abstract table class which is inherited by every concrete table class. This provides vast amounts of polymorphism which I can exploit using dependency injection. If I were to follow the advice of the "experts" and have a separate and therefore unique method for each use case (user transaction) I could kiss goodbye to all that polymorphism, all that dependency injection and therefore all that reusability. If the aim of OOP is to increase reusability then can someone explain to me why this is a good idea? Excuse me while I flush such nonsense down the toilet!

I was surprised to see in a lot of codes samples where method calls from the MVC Controller to the Model included the model name, as in the following:

require 'classes/customer.class.inc'; $dbobject = new customer; $dbobject->insertCustomer(...); require 'classes/product.class.inc'; $dbobject = new product; $dbobject->insertProduct(...); require 'classes/order.class.inc'; $dbobject = new order; $dbobject->insertOrder(...);

The problem is that those methods contain unique names which cannot be shared, therefore they are not available for reuse via polymorphism. Any code which contains those method calls is tightly coupled to the specified Models, and tight coupling is supposed to be a bad thing.

In order to increase reusability these method names should be made generic instead of specific in order to make them sharable via polymorphism, as shown in the following:

$table_id = 'customer'; ..... require "classes/$table_id.class.inc"; $dbobject = new $table_id; $dbobject->insertRecord($_POST); $table_id = 'product'; ..... require "classes/$table_id.class.inc"; $dbobject = new $table_id; $dbobject->insertRecord($_POST); $table_id = 'order'; ..... require "classes/$table_id.class.inc"; $dbobject = new $table_id; $dbobject->insertRecord($_POST);

This is an example of loose coupling which is supposed to be a good thing. The code which provides the identity of $table_id is specified within a component script while the code which processes that selection is held within a reusable controller script. Note also that I do not split the $_POST array into its component parts for reasons discussed later in Don't use separate Properties for each table column.

When writing an OO application the starting point is the creation of classes, known as encapsulation, which is then followed by inheritance and polymorphism. After you have identified an entity which will be manipulated in the business/domain layer of your application you create a class to hold all the data for that entity as well as all the operations that will be performed on that data. Note the use of the word "all" which appears twice in that statement. This means that you should not spread the data across several classes, nor should you spread the operations across several classes. The words "as well as" mean that you should not put the data and the operations in separate classes, they must always be bundled together. The logic of this statement was so simple I thought it would be easy for everyone to follow, yet some people who think they know better have found a way to cock this up.

In my opinion the prime cause for this mistake was Robert C. Martin's Single Responsibility Principle which was worded so ambiguously that it spawned a plethora of mis-interpretations which has led to it being corrupted beyond all recognition. In his first attempt at describing this principle in SRP: The Single Responsibility Principle in 2007 he started by saying:

This principle was described in the work of Tom DeMarco and Meilir Page-Jones. They called it cohesion. They defined cohesion as the functional relatedness of the elements of a module.

He then attempts to redefine cohesion using different words, but makes a complete dog's dinner of it up by coming up with:

A CLASS SHOULD HAVE ONLY ONE REASON TO CHANGE.

This caused huge amounts of confusion as the words "reason to change" are so ambiguous and have been subject to a plethora of different interpretations, each one crazier than the last. He tried to clear up the confusion in 2014 by producing The Single Responsibility Principle in which he wrote:

What defines a reason to change?

Some folks have wondered whether a bug-fix qualifies as a reason to change. Others have wondered whether refactorings are reasons to change. These questions can be answered by pointing out the coupling between the term "reason to change" and "responsibility".

What is the program responsible for? Or, perhaps a better question is: who is the program responsible to? Better yet: who must the design of the program respond to? This principle is about people.

Excuse me! The principle of cohesion has absolutely nothing to do with people, it is about functional relatedness. When I am writing code for a program I never concern myself with who will be given permission to run it as that is an entirely different responsibility which will be handled by the Role Based Access Control (RBAC) system which is built into my framework.

As neither of these answers provide a workable description of cohesion they are totally useless as a guide to programmers and should be ignored. The only workable description was provided layer in that article when he wrote:

This is the reason we do not put SQL in JSPs. This is the reason we do not generate HTML in the modules that compute results. This is the reason that business rules should not know the database schema. This is the reason we separate concerns.

This echoes what he wrote in Test Induced Design Damage? which was published earlier in the same month:

GUIs change at a very different rate, and for very different reasons, than business rules. Database schemas change for very different reasons, and at very different rates than business rules. Keeping these concerns separate is good design.

This answer made sense to me as it described the GUI, business rules and database access as being different areas of responsibility which makes them candidates for being placed in their own dedicated modules. Surprisingly this also matches the description of the 3-Tier Architecture which I had encountered in my previous language and was the foundation for the framework which I redeveloped in PHP. I say "surprisingly" as this architectural pattern had existed many years before Uncle Bob wrote his first article on SRP, but he made no mention of it even though the ideas were identical.

You may have noticed that in those two papers he wrote on the subject of SRP he makes the statements This is the reason we separate concerns

and Keeping these concerns separate is good design

This proves that Uncle Bob himself regards SRP and SoC as being equivalent

Encouraging programmers to split up a large monolithic code base into smaller modules based on functional relatedness is one thing, but any benefits obtained from such an exercise can be completely erased if a poorly trained programmer does not know when to stop this splitting. Just as encapsulation states that ALL the operations and ALL the data for a particular entity should be placed in the SAME class, once an area of program logic has been identified then all the related functions should be placed in the same module, thus fitting the description of high cohesion. Splitting a cohesive module into ever smaller modules until it is physically impossible to split it any further, as advocated by Uncle Bob himself in One Thing: Extract till you Drop, makes the code more difficult to read and more more difficult to maintain, which is the total opposite of what should be achieved.

A large number of programmers take the phrase a module should only have a single responsibility

and redefine it as if a module has more than one responsibility then it does too much

, then, because they either ignore or don't understand the meaning of the word "responsibility" (which is the same as "concern"), they translate does too much

as being based on the module's size instead of its contents being functionally related. This causes them to create large numbers of small classes where each class has only one or two methods and each method has only one or two lines of code. Even worse is when they decide to spread these dependent classes across a hierarchy of subdirectories in the file system. I don't know about you, but personally I find the prospect of searching through hundreds of classes spread across dozens of directories just to find one line of broken code to be a painful exercise.

I do not tolerate such nonsense in the RADICORE framework. I treat the generation of HTML and the generation of SQL as being separate responsibilities and have separate modules for each. While these two modules contain several thousand lines of code each, the contents of each one are functionally related and therefore match the description of high cohesion and the 3-Tier Architecture. Size is not a determining factor.

The worst examples of the practice of too much separation I have seen in several third-party libraries dealing with emails which I have installed using composer, particularly SwiftMailer and the later Symfony Mailer which replaced it. In both cases the code which I downloaded consisted of hundreds of classes which were spread across a hierarchy of dozens of subdirectories. Each of these classes contained no more than one or two methods, and each method contained no more than one or two lines of code. I once tried to track down a bug in one of them, so I fired up my interactive debugger and stepped through the code one line at a time. At the end of 30 minutes I had gone through 100 classes containing minuscule methods without seeing the code which produced the error which meant that I couldn't fix the error. This is the opposite of what good programmers are supposed to achieve. In my world an email is a single entity which should require no more than a single class. As there are different mechanisms for sending an email I would have no more than one class for each of those mechanisms. So if an email library contained four transport mechanisms it should contain no more than five classes. This would produce fewer places to search through when looking for an error which would make it easier to fix an error.

This topic is discussed further in the following:

When I first started work on my framework I scoured the internet looking for advice on how to improve the quality of my code, but sadly I have given this up as a fruitless exercise as the majority of this advice is just plain wrong because it reduces the ability to create reusable code. Some of this is down to a mis-interpretation of a perfectly valid rule, such as the following:

An invalid object is one that cannot respond meaningfully to any of its public operations.

This is perfectly clear and unambiguous, but someone else comes along and rephrases it using different words which can be mis-interpreted, such as:

A class constructor must not leave the object in an invalid state.

Unfortunately they fail to realise that in this context the word "state" means "condition" and not "the state of its data". It refers to the condition of the object itself and not the validity of any data (state) which it may contain. This is then taken to mean that all data must be pre-validated BEFORE it can be inserted into the object. In the MVC architecture this means that validation must take place in the Controller instead of in the Model. This I will NOT do for the following reasons:

This raises two questions which need to be answered:

When you consider that all data which is included in the $_POST, $_GET and $_REQUEST variables appears as an associative array where all the values are strings it is vitally important that you check that the value is suitable for the datatype of the corresponding column in the database. You can do this by using functions such as is_numeric or the filter function. If you do not there is a possibility that the generated SQL query will fail due to a type mismatch. Note that it is not necessary to manually convert each value to the correct type as PHP's inbuilt Type Juggling feature will perform this conversion automatically in certain contexts.

Those programmers who are experienced with databases will be aware that it is possible to extract a list of columns and their datatypes directly from the INFORMATION SCHEMA within the database. This list can then be utilised to identify what tests are necessary on the input data. Note that while today's programmers are taught to use annotations or attributes to provide this metadata I do not as I created a superior mechanism over 20 years ago using PHP 4.

It is not necessary to perform this level of validation until just before the relevant SQL query is constructed and executed. There should not be any opportunity between these two steps to change the data which has been validated. This rule is enforced by the framework as there is no gap between the validate() and store() operations, as shown in the common table methods which are inherited from the abstract table class.

Note what I have described above I refer to as primary validation which is performed automatically by the validation object which is built into the framework. This does not need any effort from the developer other than ensuring that the table structure file for that table is kept up-to-date with the table's physical structure.

Secondary validation, which covers the business rules for that table, will need to be inserted by the developer using any of the predefined customisable "hook" methods.

For more information on this topic please refer to How NOT to Validate Data.

In quite a few of the code samples which I encountered during my learning phase I saw where the Controller communicated with its Model using separate methods for load(), validate() and store(). I immediately saw this as a bad idea as I had learned decades before that when you had a group of functions that were always performed in exactly the same sequence then it was far more efficient to place that group in its own function so that you could process that group with a single call instead of separate calls. This reduced the amount of code you had to write in order to call that group, and it also made it easier to modify the contents of the group function without having to modify all the places from where the group function was called. It also made it impossible for the unwary programmer to place additional code between the validate() and store() operations which could potentially cause the validated data to be corrupted.

It was also obvious to me that a single store() function was not a good idea as the rules for INSERT, UPDATE and DELETE operations are completely different, as are the rules for validating the data for those operations. This is why in my abstract table class I created separate methods for INSERT, UPDATE and DELETE. The observant among you should notice that as well as the standard boilerplate code which is common to all database tables I have included references to numerous customisable "hook" methods so that unique business rules can be added to individual concrete subclasses.

If you examine the common table methods which I created in my abstract table class you will see examples of some of the group functions which I created, namely insertRecord(), updateRecord() and deleteRecord(), which perform the low-level operations in the following way:

load() is taken care of by the first argument on each call passing in the entire contents of the $_POST array.validate() is in 2 parts - primary validation using the standard validation object and secondary custom validation using code that has been placed in the relevant "hook" methods which have the "_cm_" prefix. store() will be performed by calling the relevant "_dml_" method to update the database, but only if the validation does not show up any errors.You should see that the number of methods in each group is easily expanded to cater for various circumstances without amending the code in the reusable Controllers which call them.

Another problem with having separate methods for load(), validate() and store() is that it is possible for a programmer to modify a object's property after a call to validate() and before the store(), which could lead to invalid data being written to the database. This is not possible when these two methods are processed as a group as the calling program cannot interrupt the call and alter its processing. This means that the data returned by the validate() method cannot be altered before it is passed to the store() method.

Time and time again I see sample code on the internet which, in a database application which utilises the MVC design pattern, advocates the following:

These two practices tell me that the author is still a junior when it comes to OOP as he has yet to master the art of spotting patterns in his code from which he can then create reusable and sharable components. Since a major motivation for object-oriented programming is software reuse, the inability to spot code which can be reused is a major red flag. Those of you who have read Designing Reusable Classes, which was published in 1988 by Ralph E. Johnson and Brian Foote, will be aware of the practice known as programming-by-difference in which the skilled observer notices patterns of similarities of either structure or behaviour in the code which can be separated from the differences and placed in reusable components. For example, if you spot multiple objects which share the same protocols then the recommended action is to move those protocols to an abstract class which you can then share through inheritance. The use of an abstract class then enables the use of the Template Method Pattern which allows the sharable code to be interspersed with blank "hook" methods which can be overridden in any concrete subclass to provide custom logic.

As mentioned above in Don't create a separate Method for each Use Case my design was centered around some basic facts concerning database applications which I had observed during my 20 years of previous experience:

The idea of having a single Controller which is responsible for several transactions is something which I first encountered in my earlier COBOL days, but I ditched this idea when I had to modify the code to deal with Role Based Access Control (RBAC) which required a user's access to a particular transaction to be blocked unless that user had been given permission to access that transaction. This required inserting code into every Controller before each transaction call, but this proved to be time consuming and prone to error. Instead I chose a different approach - make each transaction have its own mini-controller and have the transaction calls moved to a single place in the framework. The framework then handles the display of all the menu options, and if the user does not have access to a transaction it is removed from the menu display and the user cannot select it. Creating a single Controller which is responsible for several transactions causes two problems which an experienced develop should learn to avoid:

My solution does not have these problems. Instead of having a multitude of non-reusable Controllers which perform several transactions on a specific Model I have created a small library of 45 reusable Controllers, one for each Transaction Pattern, where each performs a single transaction on an unspecified Model. The identity of the Model(s) is supplied at run time. I achieved this by following these simple steps:

Because the definition of the resulting HTML document is controlled by a mixture of XSL stylesheet and screen structure file I can compose that mixture using a single View object which is built into the framework. This means that every transaction that has HTML output can call the same generic View object without requiring the developer to create one which is specific to that transaction. When a transaction is created by linking a Transaction Pattern to a database table two different scripts will be added to the file system:

After being created the transaction will appear in a menu screen so that it can be run with basic behaviour which includes primary data validation. Additional business rules can be included by inserting code into the relevant "hook" methods in the table class.

While reading Chapter 13. Classes and Objects in the PHP4 manual I noticed that class properties could either be defined as scalars or arrays. I also noticed that when receiving a request, whether it be from a POST or a GET, the request parameters were always presented as an array of scalars with string values instead of individual scalars with their own data type. I also read the section on Type Juggling which clearly stated that even though all the request parameters were presented as an array of strings it was not necessary to convert each individual value to a specific type before they could be used in a PHP function as the language was clever enough to automatically convert any argument to the correct type. Note that this conversion will be performed within the function itself while outside of the function the argument's type will be untouched. This means that it is not necessary to manually convert each variable to the correct type as PHP will perform the conversion automatically. However, it is necessary to insert code to check that each variable contains a value that CAN be converted to the correct type without the loss of any data and to reject it with an suitable error message if it cannot.

I also noticed that in all the sample code I read in books or online tutorials that the code which received the request (the CONTROLLER in MVC) and passed the parameters to a domain object (the MODEL in MVC) always split the array into its component parts so that they could be loaded one at a time into the domain object. This puzzled me as I wondered why, if the data from the user interface comes in as an array, is it split into its component parts before being inserted into the domain object one at a time? Is it possible to pass the data around in its original array form?

As I became familiar with the benefits of polymorphism and its contribution to the production of reusable code I realised that any piece of code that contains hard-coded references to particular column names is automatically tightly coupled with the domain object that contains those columns. This then shuts the door on any possibility of polymorphism as it cannot be reused with a domain object that does not contain the same set of columns which, as any database designer will tell you, is a virtual impossibility. Contrast this with an example of loose coupling where the Controller communicates with its Model WITHOUT referring to either the Model's class or any of its properties by name, thus guaranteeing that the same Controller can perform the same operations on any Model with any set of columns.

Having all the application data in an object available in a single array property is the main reason why I can have a single View object which can extract the data from any Model with a single getFieldArray() function and copy it to an XML file prior to it being transformed into HTML using the XSL stylesheet which is specified in the screen structure file. This is because it does not need any code to extract the data one column at a time as it has no knowledge of the column names that may exist within that object. This is an example of the benefits provided by loose coupling rather than the restrictions of tight coupling.

Another advantage I have found by using a single $fieldarray variable to hold application data within an object is that I am not limited to only that data which belongs to that object's underlying table. It can hold data for a single row or multiple rows. It can hold a subset of that table's data or data belonging to several tables obtained from an SQL JOIN. It can even hold pseudo-columns, which are prefixed with the characters rdc (for RaDiCore), which can affect how individual rows are processed.

For more information on this topic please refer to Separate properties for database columns are NOT best practice.

The visibility options were added to PHP to support the notion that encapsulation means data hiding, but as far as I am concerned this is a ridiculous idea. I have always understood the definition of encapsulation to be quite clear and unambiguous:

The act of placing data and the operations that perform on that data in the same class. The class then becomes the 'capsule' or container for the data and operations. This binds together the data and functions that manipulate the data.

This states quite clearly that data is enclosed within a capsule, not hidden. My view is not as heretical as my critics make out as it has been shared by several others:

When I investigated where the idea of data hiding originated I discovered that it was based on something which D. L. Parnas wrote in his 1972 paper called On the Criteria To Be Used in Decomposing Systems into Modules in which he wrote:

The second decomposition was made using "information hiding" as a criterion. ..... Every module in the second decomposition is characterized by its knowledge of a design decision which it hides from all others. Its interface or definition was chosen to reveal as little as possible about its inner workings

This states quite clearly that the design decisions being hidden are concerned with its inner workings. Remember that a method in an OO program is just the same as a function in a non-OO program. It has a signature which identifies what it does along with the necessary input and output arguments. The data will be identified in these arguments, but the inner workings, the code behind the signature, will not be revealed. When a function is documented the published API will reveal two things:

What a function does is fixed within its code and never varies. The data, which is input and output using arguments in its signature, is transient and can vary from one function call to another. At run time the code which calls that function also supplies the data required by that function, therefore the data cannot be hidden from the calling program. It is only the implementation of that function, the code behind the call, which is hidden. It appears that far too many people have latched onto the term "information hiding" and interpreted the word "information" to mean "data" whereas it has been clearly been stated that what is hidden is nothing more than the "inner workings" and not the data which is processed.

The data which is supplied by and returned to the calling program as arguments on a method call cannot be hidden. As mentioned above I Do not use separate Properties for each table column so all application data, typically the entire contents of the $_POST array, is passed to an object as the first argument in every method call as shown in the common table methods. The same array is returned in full to include any changes which may have been made within that method call.

The only significant difference between a procedural function and an object method is that when a function terminates it effectively dies. It does not maintain its state, so it is not possible to examine or alter is contents, only to repeat the call with a different set of input arguments. Calling a method on an object is different as the object does not die when the call finishes, so the data within it, its state, is available for the next method call. It is also possible to read or write any object property which is marked as public without using a getter or a setter. Within the object all application data can be referenced using $fieldarray['property'] instead of $this->property, so there is no loss of functionality. The advantage is that the same method call can be made on any object regardless of the data items which it handles as the calling program never has to identify any of those items by name. This is how loose coupling is supposed to be implemented.

When I first read about the visibility options I took an instant dislike to them because they do not add any value to the code, they just place artificial restrictions on what the programmer can do. As my framework works without the use of such restrictions I see no advantage in using them, so implementing them would be a waste of time, all cost and no benefit. I also disliked the levels of visibility, public, private and protected, as they do not reflect the levels of access that I see in the outside world. When a member of the public enters certain buildings they are allowed access to the public areas. The next area which is only accessible by members of staff is marked private or staff only. The level above this which is only accessible by members of staff with the relevant permissions is marked as restricted or authorised personnel only. Whoever chose the visibility levels for OOP did not follow the corresponding levels in the outside world as the non-public levels have been swapped around, so they run in the sequence public->protected->private instead of the more logical public->private->protected. As these visibility options are out of touch with the similar privacy options the real world and offer no benefits, only restrictions, I consider them as being the product of a weak mind and unworthy of consideration.